Targeting treatment resistance in ovarian cancer

Funded by Wellbeing of Women, Dr Rachel Pounds has been investigating why some of the most common ovarian cancers return and become resistant to treatment, and how this could be side-stepped.

Wellbeing of Women, in partnership with Artios Pharma Limited, has invested £447,279 in Dr Patricia Roxburgh’s research to understand how, why and when some advanced ovarian cancers become resistant to a type of treatment called PARP inhibitors

Funded by Wellbeing of Women, Dr Rachel Pounds has been investigating why some of the most common ovarian cancers return and become resistant to treatment, and how this could be side-stepped.

Wellbeing of Women and the British Gynaecological Cancer Society have invested £30,000 in Dr Maria Paraskevaidi’s research to develop a faster and more accurate diagnosis and treatment of cervical and vulval cancer

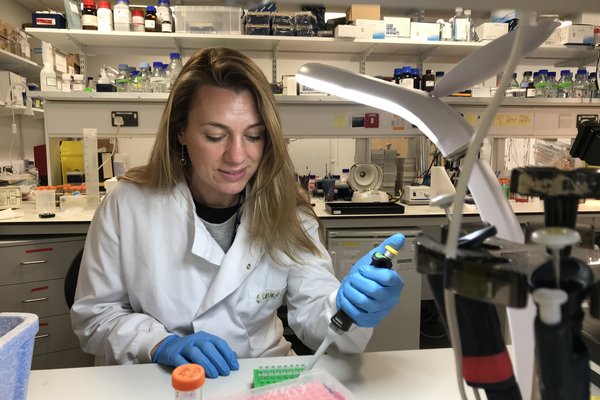

Wellbeing of Women has invested £134,193 into Dr Sarah McClelland’s research into preventing chemotherapy resistance in ovarian cancer