Can menstrual fluid identify causes of heavy periods?

A study funded by Wellbeing of Women aims to discover if heavy periods can be confirmed by a non-invasive test to help women get the right support and treatment sooner.

Funded by Wellbeing of Women, Professor Gordon Jayson has been investigating why some women don’t respond well to Avastin (bevacizumab).

A study funded by Wellbeing of Women aims to discover if heavy periods can be confirmed by a non-invasive test to help women get the right support and treatment sooner.

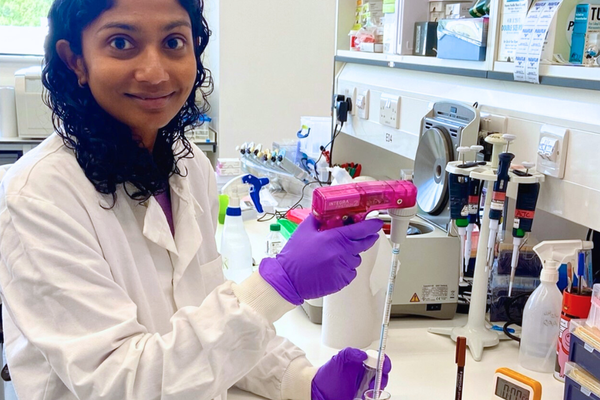

Funded by Wellbeing of Women, Dr Jacqueline Maybin has been investigating a new way to detect heavy menstrual bleeding by examining oxygen levels and blood vessels in the lining the womb.

Funded by Wellbeing of Women, Dr Roseanne Rosario is seeking to understand the connection between a genetic mutation and premature ovarian insufficiency, which could hold the key to new treatments.